|

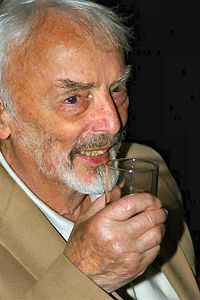

James Murray Cook 22.6.1924 -

25.1.2014

Old soldiers never die,

they only fade away,” was very true of James Murray

Cook, known to his friends as Murray, and, for a while

in Maybole, as The History Man.

He earned a reputation in his home town as the “go to”

person for anyone interested in the town’s history,

which was partly earned through his career, one that

spanned at least 30 years, as a brilliant public

speaker.

Murray was Honorary President of Maybole Historical

Society, of which he was a founder member, and which was

part of the reason that he received a Scroll of Honour

from Maybole Community Council. He also served on the

community council.

It says something about his value to the historical

society that, as Honorary President, he was the only

permanent member of its committee. That value was based

on his deep personal knowledge of the town but also his

firm grasp of the Scottish and European history that it

fitted into, in turn a result of being extremely well

read in those subjects.It helped, too, that he was a

broad-minded individual who had a philosopher’s ability

to take a detached view of people and their behaviour,

combined with empathy for his fellow men and women. His

version of history was balanced and rounded. |

|

|

His motivation was

not king and country, nor “public men nor cheering crowds” to quote

Yeats. Rather, it was a very personal belief that evil in the form

of Fascism was on the march and that the only honourable thing to do

was join the fight against it. So it was that he lied about his age,

ran away from home and joined up at the age of 17 in 1942. He had,

as he later wrote, “about as nasty a war as he could stomach” of

which the following is a very brief summary.

Wounded and captured in his first engagement with 1st Battalion

Paratroop Regiment in north Africa, three years spent in a Prisoner

of War camp in Poland, escape from a marching column as the inmates

were being evacuated due to Soviet advances and then eventual

return, courtesy of the Red Army, to Britain.

The nastiness to which he referred was without doubt the horrific

cruelty and suffering that he witnessed a good deal of, more even

than the personal pain and discomfort that he experienced, bad as

that was. It is characteristic that in his entry in the book

produced by the community council, “Maybole Memories World War II”

he chooses to recount a farcical episode a few days before his

capture. A man capable of great passionate commitment, he seldom

lost for long his appreciation of the ridiculous. After the war he

was stationed in British Mandated Palestine prior to the creation of

the State of Israel, in what was essentially a policing role.

On his mother’s death, soon after the war, he ran away to London, to

a friend’s house, unable to cope and “stared at a wall for three

days.” He had left the army with un-diagnosed Post Traumatic Stress

Disorder, which was no doubt common and which made him unable to

make use of the Government’s offer to allow returning service men to

study for a degree. In 1940s Britain he was another angry young man

with a tendency to drink.

His saviour came in the form of Liz Macpherson, whom he met when

they were both employed at St Thomas’s Hospital in London, where he

worked in the department sterilising equipment, and she was a

Theatre Nurse.

Desperate to settle down and have a family, he did so happily until

he had to face the greatest tragedy of his life; the death, at the

age of 9, of his first son, Quentin in 1964, from a measles

infection. This was a blow from which neither of them fully

recovered.

Above all, he was a family man who spent what little free time he

had with his wife and children. The “Glasgow Fair Fortnights” at

Maybole Shore with his wife, his children, and his closest friends,

including his brother Tom were precious to him. It was difficult for

him to keep in as much contact as he would have liked with his

extended Cook and Murray relations due to his job, which was a real

regret.

For over 20 years, Murray worked six days a week at Jellieston Farm,

by Martnaham Loch, for most of that that as a Pigman running the

piggery. The demanding exercise and fresh air suited him but not

much else. He always regretted the way he had to treat the animals

and for years afterwards avoided eating pork. He became a good

friend of his employer, Ewan Frazer, and his family.

For a few years after that he was a care officer at the List G

residential school, Lumsden House, in Maybole, again becoming a good

friend of his employer, Robin Dalrymple and his family.

Due to his determination to fight in the war he got off on the wrong

foot professionally speaking. His real talent was communicating to

audiences. Much as he enjoyed his own company and the solitary

pursuit of reading, he thrived in limelight, being a natural

performer like his father Jimmy. He was a member of Carrick Speakers

Club for a great many years, gave innumerable addresses at Burn

Suppers and St Andrew’s nights, and was for several years the judge

for the annual Jean Falconer Literary Competition open to the pupils

of Carrick Academy.

In retirement, he was able to follow his wider interests in music,

the visual arts, and cultural activities generally, with a group of

like-minded friends. He leaves behind a daughter and three sons.

A collection taken at the funeral

raised £404 which will to go to Prisoners Abroad. |