|

|

|

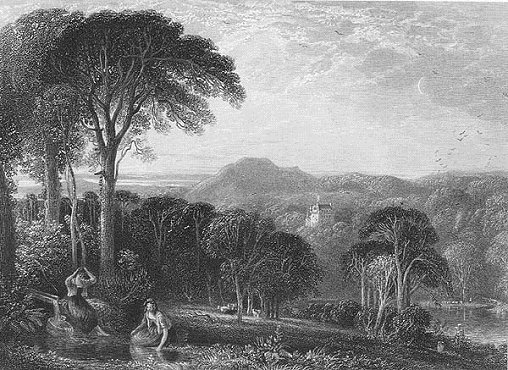

Cassillis castle continued to be the principal residence of the family till the extinction of the male line in 1759, when the titles were adjudged to Sir Thomas Kennedy, of Colzean, and that house, elsewhere noticed in the present work, became, in the language of old writs, the principal messuage of the Earls of Casaillis. Cassillis castle, although deserted by its noble owner, has never been allowed to fall into decay. A few years ago, although not well furnished, it formed a superb and perfectly entire and unaltered specimen of the baronial towers of the fifteenth or sixteenth century, containing one large apartment in each floor, accessible by a spiral stair, and having walls in some places twenty-two feet thick. Lately, it has received a new front, in Gothic taste, containing a dining-room, and drawing-room, with other apartments, and is now occupied by a gentleman on lease. The Countess"s Room-a small chamber in the upper floor, from which tradition represents the unlucky lady above-mentioned as compelled to behold her lover and more than a dozen of his companions hanging on the Dule Tree below-is still shown, but is reduced to be the sleeping-room of the servants. The grounds are laid out in a modern taste, and, with the Doon stealing its way through them, are eminently beautiful. The Cassillis Downans are three or four small hills rising about a quarter of a mile to the south of the castle, near the road between Maybole and Dalrymple. The largest- that nearest to the house,-appears to be three hundred feet above the level of the Doon; the second is somewhat lower; and one or two others are greatly less marked. They are covered with green sward, through which, in some places, the rock may be seen; and hence Burns has described them, in a note, as "rocky." On the top of the highest there is a circular mound, with a breach in it to the west, as if designed for a means of access. It is probable that this was an early fort, more particularly as the farm on the slope of the hill bears the name of Dunree-obviously Dun-righ, the king's castle. The peculiar forms of these hillocks, and their rising in the midst of a generally level country, are circumstances which could not fail to excite superstitious ideas in an unlettered people. They were, accordingly, down to Burns's time, regarded as the work of fairies, and a peculiar scene of their midnight revels. In reality, they are masses of trap, and one of them at this moment supplies excellent " metal" for the repair of the neighbouring roads. The scenery of this print must have been familiar to Burns, as he attended the school at Dalrymple for some time, during the residence of his father at Mount Oliphant. |

|

Text below from the book Carrick Days by D.C. Cuthbertson, F. F.G.S. Published in 1933. |

|

Among the bonny winding banks, IF the old-time Earls of Cassillis were Kings of Carrick, the ancient house which bears their name has seen their throne disputed on more than one occasion when the wild blood of feudal enemies was surging for vengeance. One thing I like about these old fighting days—a man had to be a man in every sense of the word or go under for all time. Bluff may carry one far in these modern times, when the law may be invoked and a full purse gains more respect than a long spear, but it was not so when the walls of Cassillis were new, and its only protection and assurance lay in the spirit of the men who warded it against all corners. At one time Dunure was the recognized home and stronghold of the Kennedys, and the winning of Cassillis is an illuminating chapter on the Carrick of bygone times. The oldest wing of the present Cassillis is said by competent authorities to date only from 1452, so that a still more ancient house must have at one time occupied the present site. Originally it was the feudal stronghold of the Montgomerie family, but, Sir Neill Montgomerie having died, for lack of an heir-male the “said lands fell to ane lass.” The Laird of Dairymple now came upon the scene as suitor, but the young lady would have nothing to do with him. The laird decided to gain the maid (and lands) by force, and so beset the house. Kennedy of Dunure, getting word of the matter, came to the rescue, slew Dairymple, and released the lady. Dunure escorted her to his sea-girt rock, and under promise of marriage she resigned her lands and possessions in his favour. It would appear that the marriage was never solemnized, and shortly thereafter the lady died. The sons of the slain Dairymple were now quarrelling amongst themselves. The youngest son, for some consideration, sold or made over his right to Dunure. This arrangement completed, Dunure “sett” for the elder son and slew him near the kirk of Dalrymple— “and thus wes Dalrumpillis conquerit.” Those were great days! When a certain laird of Dunure died the family met to decide who should be Tutor. The youngest brother declared himself to be “best and worthiest,” and so forced his brethren to appoint him to the coveted position. Alexander Dalgour was this hero’s name, the cognomen “Dalgour” being conferred because of Alexander’s facility in the use of a dagger! Now Alexander Dalgour had a quarrel with the Earl of Wigton. The Earl, anxious to settle the affair so that it would not worry him again, offered the forty-merk land of Stewarton, in Cunninghame, as a reward to anyone who would bring him Dalgour’s head. Word of this at once reached Dunure, who was nothing if not intrepid. Mounting his retainers, to the number of one hundred men, he rode to Wigton. It appears to have been Christmas morning when the Kennedys arrived, and the Earl was at Mass. It was a dangerous mission this, bearding the Earl amongst his own people, but Dalgour had made all preparations, even to the drawing up of a deed transferring the lands of Stewarton to himself, and was not a man to give undue weight to risk where his interests were concerned. Riding to the church door the Tutor went boldly in to the Earl, and holding out the deed of transfer said: “My lord, ye have offered this land to any who would bring you my head, and I know none more fit than myself. And will therefore desire your lordship to act with me as you would with any other!” The Earl, perceiving that if he refused his life would pay forfeit, took pen and subscribed the deed. Alexander Dalgour thanked his lordship, leaped on his horse, and galloped off towards the sheltering walls of Dunure. But Alexander proved too successful in the affairs of this world and grew haughty and proud. His attitude was not that of the Tutor so much as of the heir and master, and the other members of the family began to fear for the young heir’s fate. A family conference was held, unknown to Alexander Dalgour, and a plan arrived at. The verdict was that the Tutor should be smothered with a feather bed (or pillow) while asleep, a decision at once acted upon, “and thair he deit.” Brave old days !—but never a better morning for any Carrick project than this which found me tramping along the Maybole road towards Cassillis. The beech-hedges were like burnished copper in the forenoon sun, somewhere behind the trees an old cock pheasant was challenging the world, and on every count it was good to be alive. As I turned abruptly to the right at the crossing the narrow winding roadway dropped suddenly, but above the hedges I could see a rampart of distant blue hills, and the air was fragrant with wood smoke from some near-by cottage. A sloping field on the left was literally covered with peesweeps, gulls and crows. Never have I seen such a busy congregation, and although I stood at the hedge-side and watched the proceedings for quite a time, not one individual ceased from its labours; indeed, they ignored me entirely. Another rushing burn, the second within some fifty yards, and it was easy to guess how Doon maintains her flood. The road still wound and twisted, as if postponing its arrival for as long as possible, and then the open fields gave place to the woods of Cassillis. A circling bend in the roadway, and there, reserved and austere amongst its autumn setting of trees, the old house of Cassiliis, the Brown Carrick forming a suitable background. Burns mentions Cassillis in his Hallowe’en, and apparently at one time fairies danced of a moonlit evening on the Downans, or green hillocks, or galloped over the lays or fields on elfin horses: “Upon that night, when fairies light, But the most interesting feature is the old dule-tree, a wicked old monster from the branches of which were hanged those who outraged feudal dignity. It was on this tree that Johnnie Faa and his merry band expiated their crime of carrying off the Earl’s lady. The story is well known, but no chapter on Cassillis House would be complete without its inclusion, although it is only fair to mention that the facts are all against the likelihood of its being true in any respect. Chambers evidently accepted the traditional story as being founded on fact, indeed he is quite clear on the point, but while the actual facts may never come to light, it is, to say the least, doubtful. The tale as Chambers has it is that John, the sixth Earl of Cassillis, was a stern Covenanter, a man who would never allow anything he said to be misunderstood or misconstrued in any way. There was just one way with him—his own narrow, Cameronian path. A most admirable type, but an uncomfortable man to live W1th. Thomas, first Earl of Haddington, the most brilliant lawyer of his day, had by his genius amassed a fortune and been elevated to the peerage. This Earl of Haddington had a beautiful daughter, Lady Jean Hamilton, who loved and was loved by a gallant knight of about her own years, a Sir John Faa of Dunbar. Picture their consternation when one day the Earl warned his daughter to prepare for her nuptials as he had arranged with the Earl of Cassillis to give her to that nobleman in marriage! Those were stern days, and the Lady Jean had no option but to bid her lover a last farewell and become the bride of the serious, uncompromising Carrick nobleman. Some years passed, the Lady Jean had presented her husband with at least three children, and the old romantic attachment to the knight of Dunbar might well be considered a thing of the past. But that was not so, and Sir John Faa at least—I dare not cast further aspersions on the lady—had never forgotten his true love, and still nursed hopes of claiming her as his own. Then was held the Assembly of Divines at Westminster, and Cassillis was one of those chosen to attend. Sir John Faa seized the opportunity, and disguising himself as a gypsy, and accompanied by fourteen real gypsies to help him in his mission, he came to Cassillis. “The gypsies cam’ to our gude lord’s yett, And she cam’ tripping down the stair, So much did they “cuist the glamourye o’er her” that she produced white bread for them to eat, and, alas! taking off her wedding-ring, she ran off with her old sweetheart. She was no more than gone when the Earl unexpectedly returned from Westminster. On asking for his lady, the terrified domestics related what had happened. Tired and fatigued as they were from their long journey, the Earl ordered his retainers to follow, tarrying an impatient moment until fresh horses were saddled, and then galloped off in pursuit of his Countess and her lover. They had not far to go, and at a spot still called the Gypsies’ Steps the band was overtaken, and captured to a man. The Earl brought them back to Cassillis, and before the lady’s horrified eyes hanged the fifteen men on his dule-tree! That some domestic tragedy was enacted on the spot is possible, perhaps probable, but the letters written by the sixth Earl on the death of his Countess, dated from Cassillis, December 1642, are of themselves ample proof that his domestic affairs were uneventful and happy, and he mentions his loss in terms of sorrowful affliction. If a knight did upset the matrimonial routine, at one time, it is probable he assumed the name of Faa as a disguise. Faa was a well-known gypsy name, and more than one Act of Parliament was passed for the suppression of gypsies in which it is specially mentioned. In 1579 the Estates enacted against “strang and idle beggars.” The Act was expressly framed to put a stop to masterful beggars and vagrants, doubtless a serious danger in the then state of the country, and also embraced “sic as make themselves fules and are bards” and “vagabond scholars of the universities of St Andrews, Glasgow and Aberdeen.” It was an unlucky year for poets, and at least two were hanged for no other crime! Cassillis may have hanged a number of gypsies on his dule-tree, and if so he was merely carrying out the law, as a man in his position was almost bound to do. In July 1616 some members of the Faa tribe, John and James Faa, Moses Baillie and Helen Brown were arrested for remaining in this country contrary to the Act which banished all known Egyptians on pain of death. They were sentenced to be hanged. Some eight years later six members of the Faa tribe were hanged for a like offence, their wives and children liberated on condition that they departed outwith Scotland at once. Something of the kind may have happened at Cassillis, and the romantic details been added by the balladist, who knows? But love is a pale subject in a land so coloured by feuds and strife, and one of the strangest sorties in our history was conceived by the Kennedys, and staged across the Doon a mile or two from here. I have referred to it on a former occasion, but may be allowed to touch upon it in passing. The affair in question took place somewhere in the fifteenth century, the date is uncertain, and is known as “Skeldon Haughs, or the Tethering of the Sow.” The Kennedys and the Craufurds had been enemies for generations. The Doon ran between their territories, and it was good sport to cross the ford, fire a few farm-steadings and drive off the cattle. There was no appeal to law—other than the law of reprisal —after an excursion of this sort, but each side was getting wary and hard to trap, and the younger blood of Carrick was getting restive and weary for lack of excitement. One evening as old Craufurd was sitting in his castle of Kerse (not a stone remains to mark its spot to-day), surrounded by his sons and retainers, an emissary from the Kennedys was announced. It took a daring man to beard Craufurd in his own domain, and angry frowns and murmurs greeted the lad as he advanced. But old Kerse was master in his house, and his dominant glance quelled the uprising tide of anger. Curtly he asked the lad to state his business, telling him that, while he was an unwelcome visitor, his safety was assured. “My business,” replied the young scion of the Kennedy clan, “is to tell you that on Lammas Day the Kennedys will tether a sow on Skeldon Houghs, and not all the Craufurds in their might dare flit it.” At once the hall buzzed with indignation at the insult, but the fierce old man raised his hand for silence, and facing the page said: “You are a brave lad to come here on such an errand. Now go back to ‘those who sent you, and tell them that we shall be ready, and to think well before they put their hands into a wolf-trap from which they shall not escape scathless.” More than one Craufurd rose as if to follow the young messenger as, self-contained and disdainful, he bowed to their ancient chief and turned to leave the great hail. The fierce old leader ordered them to remain where they were and to molest the Kennedy courier at their risk. The fatal morning arrived, impatiently awaited be sure, and the sow, brought in a sack, was duly tethered. “Twas Lammas-morn, on Skeldon Houghs, The glintin’ sun had tinged the soughs; Frae Girvan banks and Carrick side Down pour’d the Kennedies, in pride; And frae Kyle-Stewart and King’s-Kyle The Crawfords march’d in rank and file.” The picked fighting men of Carrick and Kyle were to meet again in open conflict, and had chosen the longest day for their trial of strength, each side imperiously certain of its prowess. Kerse himself was too old to take part, but his sons were there, noted fighting men all. The long hours passed slowly for the old warrior, his heart in the conflict but his palsied arms unfitted for the sword. Now and again he could hear the angry shouts of the contestants, but no messenger brought tidings. And then as twilight was falling a horseman galloped towards Kerse, and in his eagerness for news the old chieftain ran forth to meet him. Almost before the man-at-arms had reined in his horse Kerse was anxiously calling to know if the sow was flitted. “Both sides have suffered great loss,” began the man. “Never mind the losses,” replied Kerse; “is the sow flitted?” “Your son Jock has been killed,” altered the retainer, “and——” “Is the sow flitted?” demanded Kerse. “Tell me at once.” “Yes,” was the answer, “the Kennedys and their sow are across the Doon and in full flight.” “Then ma thoom for Jock!” shouted old Kerse in unholy triumph, almost dancing with joy. “Ma thoorn for Jock, if the sow is flittit!” Alexander Boswell of Auchinleck put the tale into rhyme, and the closing stanzas are amusingly written: “‘Is the sow flitted? Tell me, loon! Is auld Kyle up and Carrick doon?’ Mingled wi’ sobs, his broken tale The youth began :—‘ Ah, Kerse, bewail This luckless day! your blythe son, John, Ah! waes my heart he’s on the lawn, And he could sing like ony merle.’ Is the sow flitted,’ cried the cane, ‘Gie me the answer—short and plain— Is the sow flitted, yammerin’ wean?’ ‘The sow deil tak’ her’s ower the water, And at their backs the Craufurds batter, The Carrick couts are corned and bitted.’ ‘My thumb for Jock! the sow is flitted.’” Reginald, first of the Kerse Craufurds, got a grant of the lands of Kerse from his brother Hugh, in the reign of King Alexander III. (1249-1286), and like their neighbours the Kennedys they loved fighting for the game’s sake. When James VI., dismayed at the disorders and feuds amongst his noblemen, and fearful that the internal strife would weaken the national fighting forces, ordered a number of the more prominent feudalists to appear before him, in the closing days of 1595, Craufurd of Kerse was amongst those singled out for the royal summons. The fields and braes look peaceful enough to-day in the autumn sunshine, and the road—one of the most winding and procrastinating I know—meanders on until at last it faces the Doon, and Dalrymple kirk comes into the view. A long narrow bridge joins Carrick and Kyle, and below the Doon was in flood, a broad drumly stream, and then the wide deserted main street of Dalrymple. Of Dalrymple Castle, stronghold of the would-be suitor of Sir Neill Montgomerie’s daughter, there is now no trace. Tradition credits Sir John Kennedy of Dunure with having had something to do with razing the walls, but this may be nothing other than romance. In any case this Sir John was the knight who slew Dairymple, abducted the maiden, and then conducted a feud with the heirs, as already shown. Naturally, the Dairymple family had no love for the strong-handed Kennedy, but he had proved his might on so many occasions that they decided to accomplish by guile what they could not achieve by force. The plan was to invite Sir John to a feast in Dairymple Castle, and once caged see that the bird did not escape. It is a striking proof of his temerity that the Kennedy not merely accepted the invitation but set out for Dalrymple accompanied only by a squire. Just as they were about to cross the drawbridge, Sir John’s old nurse, who was now a dependent of the Dairymple family, looking at her former charge audibly remarked, as if speaking to herself; what a pity it was that such a brave man should unwittingly enter a trap. At once the intended victim became alive to his danger, and hastily retreating made all speed for his own stronghold of Dunure. Calling out his men-at-arms he returned to Dairymple, slaughtered the inmates and laid waste the castle. To stand on the bridge and look across the peaceful countryside, the clustering trees concealing Cassillis and Auchendrane, a slow-moving ploughman and his team at work in the autumn sunshine, it is hard to believe that such scenes were enacted, and that only a few years ago in the history of our land no man could foretell if his roof-tree would cover his head that night. If the old Brown Carrick hill could only speak and tell of the scenes it has witnessed since the centuries were young! |